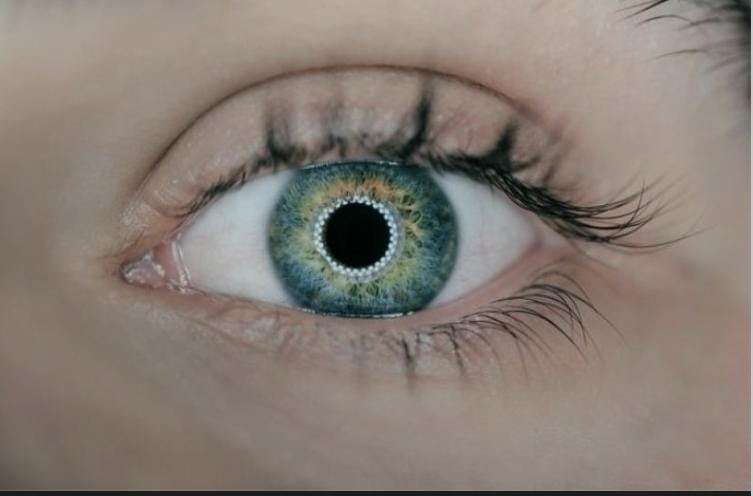

Gene therapy shows promise to help treat glaucoma

Sydney, June 28 (IANS) Australian researchers, including those of Indian-origin, have developed a technique for a gene therapy that could help treat glaucoma — the world’s leading cause of irreversible blindness.

The findings, published in the journal Molecular Therapy, showed that the treatment ensures nerve cells in the eye continue to produce a vital protein that protects them from being broken down and could help prevent the progression of glaucoma.

Glaucoma is the world’s leading cause of irreversible blindness, affecting more than 70 million people globally. It is associated with gradual vision loss, initially in the periphery but then spreading centrally.

The disease damages the optic nerve and the retinal ganglion cells — which are a type of neuron that carry visual information to the brain.

Researchers from Macquarie University investigated the role of the protein neuroserpin in the disease.

They found that neuroserpin, which is produced in the connectors between nerve cells, is vital in protecting retinal ganglion cells.

“Other researchers have linked changes in neuroserpin to stroke and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, but our work is the first to relate it to glaucoma,” said Vivek Gupta, Associate Professor and vision neurobiologist at the varsity.

“Cells naturally break down and are recycled in the body, but when neuroserpin is absent, this process speeds up in the retina. Essentially, the body begins to eat away at the retinal ganglion cells and the optic nerve,” Gupta said.

The team discovered that when neuroserpin oxidises, it loses its protective ability, allowing accelerated cell breakdown.

They also showed that when mice produce more neuroserpin, it has a protective effect, promoting the survival of the retinal ganglion cells and minimising glaucoma damage.

The team successfully manipulated a gene in mice to produce a version of neuroserpin that is resistant to oxidation.

“When we introduce this gene directly to the eye, it increases the production of neuroserpin in the retina,” said vision scientist Dr. Nitin Chitranshi from the varsity.

“Currently, that involves injecting it into the eye, which is obviously quite confronting, but we are working on a way to introduce the gene using a synthetic virus that can be targeted to specific cells in the retina.

“The artificial virus would not have any effect on the body, but would act as a carrier for the therapy, allowing our specially developed nanoparticles to get inside the cells and tell them to produce our modified neuroserpin,” Chitranshi said.

The team is now preparing for further testing of the enhanced gene and will commence new trials shortly.